Nathan Fulcher is a self-identified “white guy from Iowa.” He grew up in a small town and went to a Catholic high school with only 100 students in the whole building.

The world of Fulcher’s upbringing couldn’t be any further from that of Santa Monica High School on Los Angeles’ west side, where today he teaches language and literature. With roughly 3,100 students in all nine-12th grades, Fulcher says the school’s greatest strength, and at times its biggest source of conflict, is the diversity of the student body.

“I want to ensure that my students are capable of talking about race in a thoughtful and respectful way.”

— Nathan Fulcher

One of the courses that Fulcher (BA ’03) instructs is a senior African American literature elective, and given the subject matter, race is in the foreground of many class conversations. In his instruction, Fulcher uses historical literature to contextualize current events for his students and illuminate the perspectives that exist around race.

“We read the play, The Ballad of Emmett Till, and it really gets to my students,” Fulcher says. “The play became even more relevant a few years ago in light of the Trayvon Martin case. Many of my students struggled that year trying to understand a play set 50 years ago while seeing the parallels play out in the online news.”

Some colleagues were surprised when Fulcher first expressed interest in teaching African American literature, but for him, the subject built upon what he studied at the University of Iowa. Fulcher focused his major in African American literature, and the Harlem Renaissance was the subject of his final student-teaching project.

Through Fulcher’s experience as a white teacher instructing African American literature to diverse students, he emphasizes the importance of modeling the dialogue for students when issues regarding race arise.

“So often we are afraid to even have the conversations, so we tip-toe around them so as not to offend anyone. Or, we speak in broad generalizations and don’t get anywhere,” says Fulcher. “I want to ensure that my students are capable of talking about race in a thoughtful and respectful way when they leave my classroom.”

In his classes, Fulcher is honest about his upbringing and identity. By confronting issues directly, he creates a safe space for his students to express their own identities and explore issues involving race.

“I’m open with my students about who I am and what I believe, and they see that passion come through in my teaching,” Fulcher says.

Fulcher’s experience growing up in a largely white community and later teaching at a vastly diverse school models what is becoming more and more the norm: across the nation, the racial make-up of K-12 students is changing, with more schools looking like Santa Monica High, and less like that of Fulcher’s youth.

In 2014, for the first time ever, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reported that minority students outnumbered non-Hispanic whites in K-12 schools. Yet while the racial makeup of America’s schools is evolving, the NCES also reported that nearly 80 percent of all public school teachers and 90 percent of private school teachers identify as white.

Through his work as a consultant and director of the White Privilege Conference, an annual event that examines “challenging concepts of privilege and oppression,” Eddie Moore, Jr. (PhD ’04) focuses his work on the evolving dynamics of diversity, power, privilege, and leadership in educational systems.

“If you come from a place where you haven’t had a lot of diversity exposure, it doesn't make you bad, it just makes you ill-prepared.”

— Eddie Moore, Jr.

“The world that our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents grew up in during the 20th century is just not the world of the 21st century,” Moore says. “We know people need global competency skills just to be productive and effective.”

Through his consulting firm America & Moore, Moore works with a variety of different stakeholders — teachers, students, parents, administrators — to positively impact systemic issues involving diversity, power, and privilege. He says that being culturally competent and having the ability to engage in conversations around race are vital to success, not only in K-12 classrooms but also in college and the workplace.

As U.S. classrooms become more diverse, College of Education faculty, students, and alumni like Fulcher and Moore are leading the way to model best practices for talking about and teaching race in 21st-century classrooms.

As an associate professor in Higher Education and Student Affairs and the University of Iowa Chief Diversity Office’s inaugural faculty fellow, Sherry K. Watt focuses her research on innovative ways to create effective cross-racial dialogue in classrooms. She analyzes methods of engaging students and teachers across their differences, particularly in relation to race.

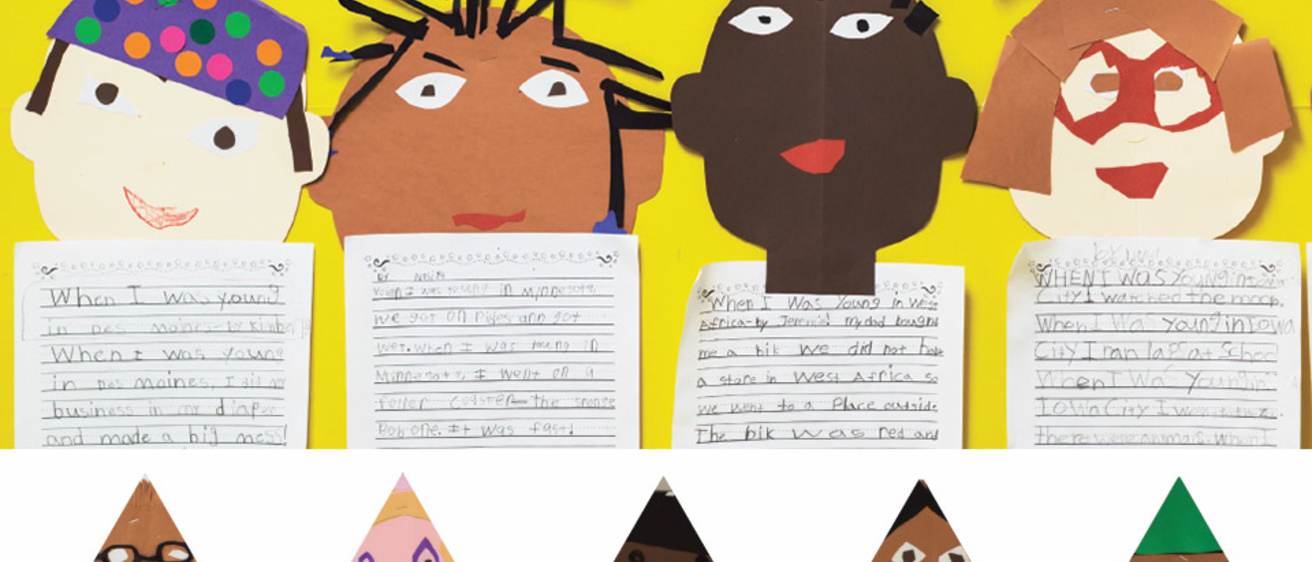

Watt says that for many people, talking about race is difficult, but she emphasizes that productive dialogue is one of the most important aspects of building greater awareness and understanding around race in K-12 classrooms and beyond. For her, one of the most productive ways to instill an understanding of diversity is by starting conversations about race at a young age.

“There’s a way to point out the complexities of the social context as it relates to race to young children so that they understand what they’re seeing and they understand that it informs the backdrop of society,” Watt says, noting that children can be more accepting of cultural difference than adults.

Beyond the K-12 setting, having conversations in college classrooms around race can be challenging. Watt teaches a graduate class called “Multiculturalism in Higher Education” where she leads students to explore social constructs like race, gender, and sexual orientation, as well as how to model conversations around those topics. She says this class has been powerful in guiding students to understand privilege, the deep roots of racism throughout American culture, and the importance of dialogue across difference.

“One of the saddest things I see is when white graduate and undergraduate students tear up and say that nobody ever told me this before, nobody ever told me that I live in a racist, sexist system,” says Watt.

Watt’s students take her lessons with them after graduation, and she says stories of the experiences they have in their own classrooms help inform her future students.

“I always tell students on the last day of class, when you have your ‘Aha!’ moment, or you’re in the field working and all of a sudden make the connection with what you learned here and how it’s impacted what you’re thinking about your life or your work, send me a note back, because remember: I’m back here working with the students that are struggling with or resisting conversations around race, and it will help all of us to know that this educational experience makes a difference” says Watt.

Elizabeth Getachew, a doctoral student in Schools, Culture, and Society, teaches undergraduates studying to become teachers, and through her work she emphasizes the importance of looking for the good in each person, regardless of their background or culture.

“I teach college students to understand each individual person, each student as their own, and not to classify their students as black, Hispanic, white, rich, or rural,” which Getachew says helps students break down stereotypes.

When Moore speaks with universities and constituents preparing for work in the field of education, he emphasizes the importance of learning about diversity and obtaining cultural competencies.

“I approach the diversity work from a skill-based perspective. It’s not about blaming people, shaming people, degrading people, pointing people out as bad, evil people,” Moore says. “If you’re coming out of a place or you come from a place where you haven’t had a lot of diversity training, or diversity exposure, or cultural competency opportunities, it doesn’t make you bad, it just makes you ill-prepared.”

But Moore warns that as the U.S. economy becomes more global and the workforce more diverse, the inability to work with people of different backgrounds could be detrimental to success.

“If you lack global cultural competency skills in the 21st century workplace it could cost you your job,” he says.

Moore’s message about the importance of being culturally competent and having the ability to work with people of different backgrounds is especially true for education professionals. As recent events on campuses across the country have highlighted, teachers face some of the biggest pressures to be culturally competent.

But learning about diversity later in life can mean having difficult conversations. Watt says that because many people aren’t taught to talk about race, especially beginning at a young age, when these conversations arise, they aren’t prepared and tend to retreat from the conversation in order to avoid a miscommunication that may lead to perceived racist comments, or alternatively they exhibit defensive behaviors that can inhibit productive dialogue.

Through her experiences guiding these conversations, Watt knows that the practice of patience is an essential element during these dialogues. She recommends giving all involved the permission to misstep and misspeak in order to find a collective voice. She suggests that educators start by establishing ground rules and preparing the group for inevitable emotional and defensive reactions. Anticipating these reactions and having strategies for working through them can help teachers to better manage these difficult conversations.

“I hope that there will be trust built among teams of teachers, or counselors and supervisors, or friends and family, where you have conversations with each other about where you’re at with these issues, how you can continue your development, how you can unlearn stereotypes that hinder relationships, and how you might be able to support each other when you run into a situation that you feel being triggered,” Watt says.

While working as a counselor at Linn-Mar High School in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Laura Gallo (MA ’05), a doctoral candidate in Counselor Education and Supervision, began to notice that there were misunderstandings between students of diverse background and some of the teachers in her building. She decided to initiate proactive change in her building to positively impact the school’s climate and improve the learning experience for all.

“I hope that there will be trust built, where you have conversations with each other about where you’re at with these issues.”

— Sherry K. Watt

Through her efforts, Gallo put together professional development activities — one-on-one meetings, group conversations, and interactive training sessions — that helped the counselors and teachers humanize their students and also quantify their own privilege. During one workshop, she included a survey that asked her colleagues questions like “has a member of your family ever been to jail,” which led to conversations about white privilege and helped the high school’s leaders become more in touch with the life situations of their students.

“It helps to be aware of the values and assumptions we have without really thinking about it,” Gallo says. “It can give teachers a better understanding of the students, their families, where they’re coming from, and maybe some of the struggles they have.”

Watt says that sometimes, even with the best intentions, the conversations don’t end up the way that Gallo’s did. In these moments, Watt says one of the most helpful tools can be an apology.

“Admitting that you don’t know and that you’re uncomfortable is a good first step,” she says. “It helps bring authenticity to the moment, and in that moment you can work from there towards some kind of change.”

As the 21st century progresses, it’s clear that working towards change in the nation’s increasingly diverse classrooms will become even more imperative.

“It’s not just about liking black people; it’s not just about being able to work with a black kid. In today’s classrooms, there are going to be issues of race, religion, sexual identity, and sexual orientation involved with the students, and the families, and the communities with whom you work,” Moore says, noting that educators and students must build upon and expand their skills to work with people of diverse backgrounds to successfully move toward a better future.

As to who and what defines diversity, Watt emphasizes that people need to keep learning and unlearning attitudes toward those who are different from them in terms of backgrounds, beliefs, sexual orientations, and skin colors.

“These issues continually evolve, so you have to spend time exploring them and unlearning some of the things you’ve been taught about who people are, about stereotyping, and about marginalization,” Watt says. “The ways our minds have been imprinted with positive stereotypes associated with white people and negative stereotypes associated with marginalized people or people of low income — all that has to be intentionally thought about and unlearned.”